Floodplain wetlands in semi-arid and arid regions are important habitats for a variety of wildlife, including frogs. Managing these important habitats requires that we know how wildlife respond to their patterns of natural flows, but surprisingly we don’t have a good understanding of this relationship for many species. While it makes sense that frogs would like inundated wetlands, we don’t actually know if this is the case in many systems, so I set out to determine which species were fond of good flow conditions and which weren’t. I found that while the Macquarie Marshes, a large floodplain wetland with huge conservation significance in inland NSW, supported a diverse range of frogs, not all species responded to flooding in the same way. Knowing this helps us understand which species are more likely to benefit from managed water flows, and which aren’t.

If you’ve been around frogs for a while, then you’ll know that if it has rained a lot, you’ll see and hear a whole different set of frog species than if it hasn’t. Also if it is still 26⁰C at midnight rather than 12⁰C, again the frogs that you see and hear will be quite different. Figuring out which species you are likely to see in what conditions is important, particularly when you want to determine how to conserve them; just because you didn’t see them, it doesn’t mean they weren’t there, which is especially true for burrowing frogs!

In order to determine how we might be able to manage frog populations by releasing upstream waters (in dams) to replicate natural flows (‘environmental flows’), I needed first to understand how natural floods affect different frog species living in large complex floodplain wetland systems. I wanted to make sure that any managed flows would actually benefit (or not) the frogs that live there. I also needed to know how things like temperature or rainfall or water depth affected how likely I was to see different species.

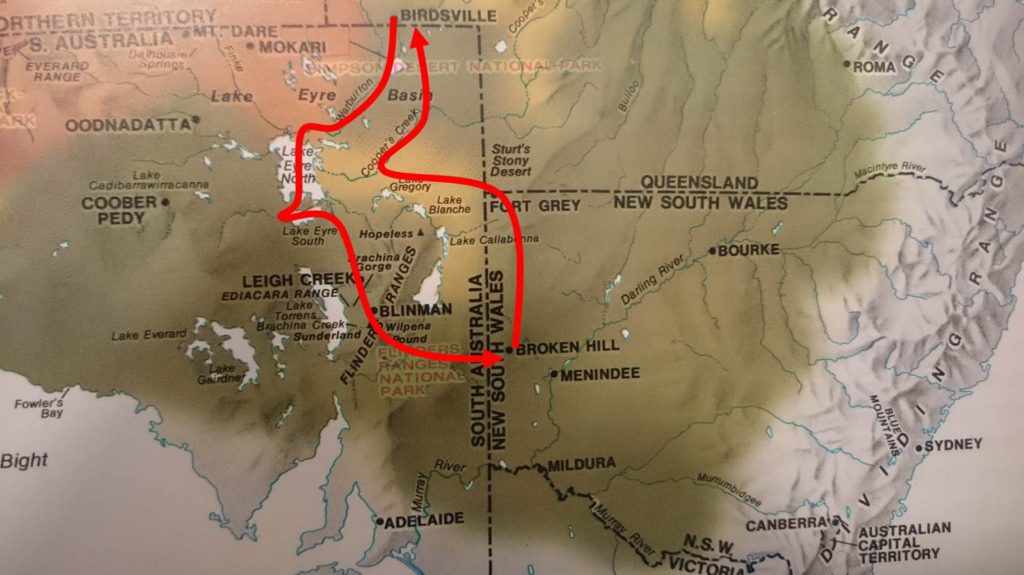

To do this, I (and my crew of amazing field assistants) spent a lot of afternoons and evenings sloshing through different parts of wetlands and around waterholes in the Macquarie Marshes in NSW. We did this during a large natural flood, and recorded data on weather, vegetation and water as well as all the frogs we came across.

During four months of surveys at 30 sites in the Macquarie Marshes, we identified 15 frog species, including barking marsh frogs (Limnodynastes fletcheri), wrinkled toadlets (Uperoleia rugosa), desert tree frogs (Litoria rubella) and Sudell’s burrowing frog (Neobatrachus sudellae). On average, we counted nearly 40 individual frogs per site, though sometimes we saw none and once four of us counted nearly 250 in 20 minutes!

Putting all that together, I found that as expected, not all frog species did the same thing at the same time or even liked hanging out in the same places during a flood. However, frogs that had similar features generally shared similar responses. Species that move around on the ground but can’t burrow, such as spotted marsh frogs (Limnodynastes tasmaniensis), were seen in most weather and site conditions, and were more abundant at temporarily flooded wetlands with some aquatic vegetation. Conversely, tree frogs, such as the green tree frog (Litoria caerulea) liked to be around wooded wetlands but needed it to warmer and rainier before they’d be out and about.

The remaining species, which had special adaptations allowing them to burrow into the soil, such as the crucifix frog (Notaden bennettii), were rather particular. They were more likely to pop up after some rain the day or night before and they weren’t very keen on the wetlands, preferring ephemeral, rain-fed waterholes.

After unlocking the secret preferences of frogs in a large floodplain wetland during a natural flood, we can now start to get more precise about how environmental water supports frogs. While burrowing frogs might not appreciate flood waters without associated rainfall, we know that ground frogs like the spotted marsh frog do. This means that these frogs are likely to directly respond to and benefit from water releases. And if you’ve got happy frogs, you’ve got a well-functioning wetland!

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to my co-authors, Richard Kingsford (University of New South Wales), Trent Penman (University of Wollongong) and Jodi Rowley (Australian Museum Research Institute). I’d also like to thank landholders and Reserve rangers for permission to access the Macquarie Marshes during this study. Funding and support for the surveys were provided by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage, the NSW Frog and Tadpole Society, and the Foundation for National Parks and Wildlife Service. For their assistance in the field, I particularly thank Carly Humphries, Jonathon Windsor, Ashley Soltysiak, Sarah Meredith, David Herasimtschuk, Angela Knerl, Diana Grasso, and Bill Koutsamanis.

For the nitty-gritty details, see:

Ocock, J.F., Kingsford, R.T., Penman, T.D. & Rowley, J.J.L. (2016). Amphibian abundance and detection trends during a large flood in a semi-arid floodplain wetland. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 11, 408-425.