When I first saw Pelobates fuscus, I was much more excited than I thought I’d be. Yes, this was a delightful if slightly dull-coloured round blob of a European burrowing frog (the ‘common spadefoot’), spotted while traipsing through a wetland in Hungary. But it was more than just a new species I could tick off my global amphibian checklist. This was a ‘pilgrimage’ species. Pelobates fuscus was the subject of several scientific articles I read early in my PhD that were important for learning theories and shaping my understanding of amphibians and floodplain wetlands. I’d read about it, studied it, and now I was looking at it!

I recently got to tick off another item on my pilgrimage list – this time the Lake Eyre Basin (LEB). The LEB looms large in the Australian psyche, but especially so if you are a freshwater junkie like myself, fascinated by how water can move across such a massive, flat, arid landscape and the life it brings with it.

A study in the late 1990s characterised 52 rivers worldwide and found the Cooper Creek and the Diamantina Creek, both in the LEB, to be the most variable for when the water flows, how much comes and how long you have to wait in between flows (i.e. flow timing. magnitude and frequency). They extended the Flood Pulse Concept (Junk 1989), which had only been applied to rivers with predictable regular flows, to include this complexity and so recognise that lots of biological processes, such as waterbird movement and breeding, fish spawning, rely on this natural variability. Again, these were paradigms and theories that made me stop and think, and became central how I understood my own research.

Now, the LEB is not exactly the low-hanging fruit of pilgrimage sites. It’s rather large (one-sixth of Australia’s landmass, or France, Spain and Portugal put together) so what counts as ‘being there’? Could I tick it off my list by just getting my foot over the line of the Basin catchment, or do I need to see Lake? What about putting a toe in the water? Also, it’s a long way away from anything. The sealed roads run out well before you get there. It’s not something you drive past on your way elsewhere, it has to be the destination. And a long weekend from Sydney is unlikely to cut it. Finally, it’s often not there. Well the water isn’t anyway. Like I said it is variable. Subject to continental-sized weather processes as well as high rates of evaporation, on average the lake only fills once in ten years.

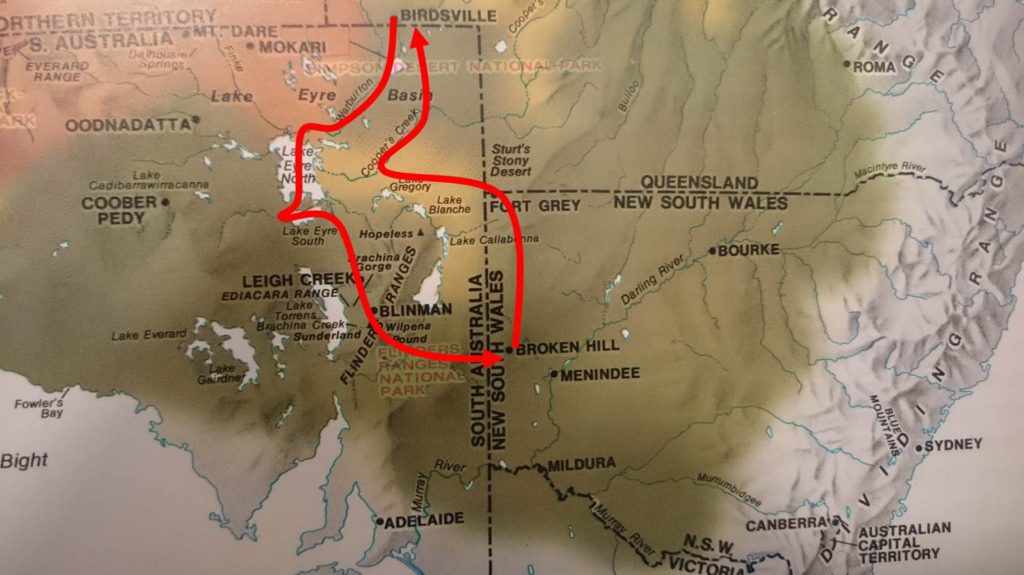

Fortunately, the weather-gods smiled on my pilgrimage to the LEB. In mid-May 2016, my parents and I drove to Broken Hill, and from there took a chartered scenic flight which followed the Cooper Creek north and stopped at the Birdsville Hotel overnight. The next day we followed the Diamantina Creek and Warburton Channel down stream before and flying across Lake Eyre to William Creek. Due to the rain across the region three days earlier and recent flows down from Queensland, there was water everywhere and the lake was about 60-70% full. A spectacular sight. I can’t adequately describe the experience of following those creeks and flying over the Lake. Really I can’t. The photos don’t do it justice. A worthy pilgrimage site, I was amazed and humbled.

Footnote: huge thanks to Drew from Silver City Air Charter for flying us around and planning the whole trip, highly recommend!