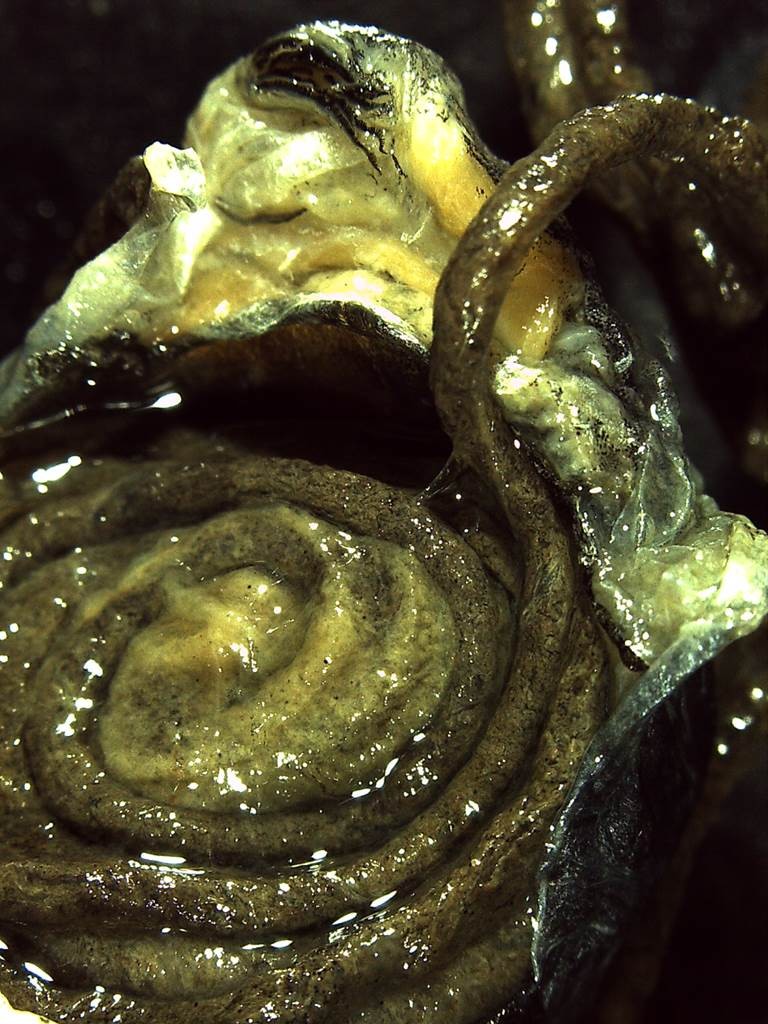

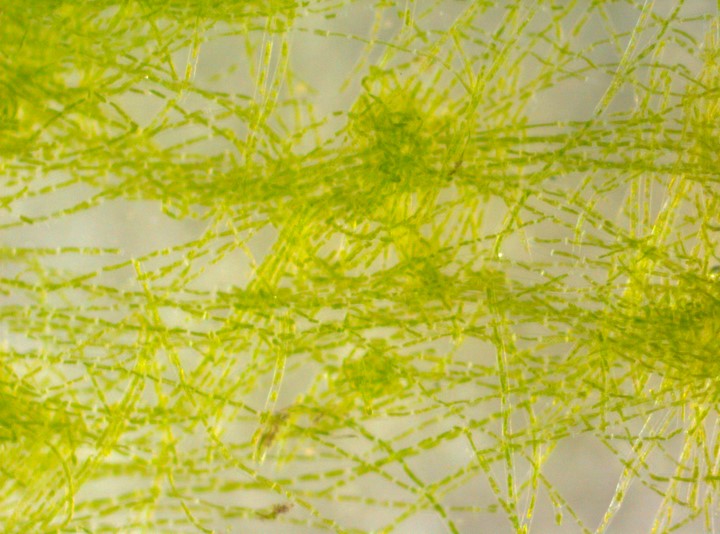

A while ago, I wrote about looking for the end of the food-chain. My co-workers and I had dissected some common species of tadpoles from floodplain wetlands and inspected their gut contents under a microscope. We had found they eat a wide variety of things, from tiny crustaceans and other small insects to bits of aquatic plants and long strands of filamentous algae.

But I wanted to know, what was the most important thing that they were eating? I’d had a feeling the answer was going to be “even smaller things”, and it turns out I was right!

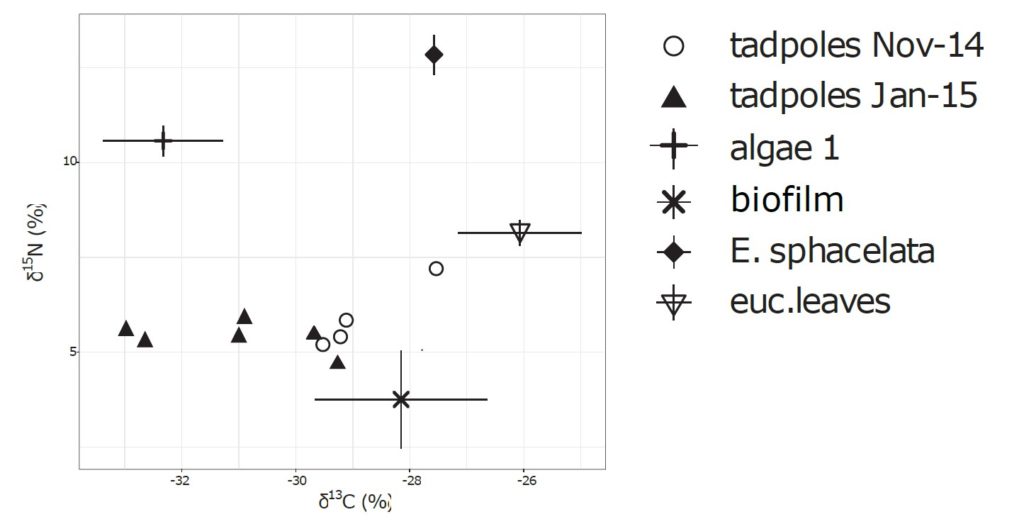

To answer this part of the question, we did a chemical analysis that compared samples of tadpole muscle tissue with samples of food items such as wetland plants, tree leaves, algae, those teeny tiny crustaceans living in the water, and biofilm. It is a method called stable isotope analysis and it works along the lines that ‘you are what you eat’. And as we report in our new research paper, these results suggested that biofilm was most important. (Twitter summary here). (Full disclaimer, we’re mostly confident that it was biofilm, in some wetlands at some times for a couple of species… check the paper for all the details, DM me for a copy).

And what is biofilm? Biofilm is basically a super nutritious mix of very small things like bacteria, microbes, fungal hyphae, and teeny-tiny invertebrates, that looks like a filmy, fuzzy goo growing on the surface of leaves and branches and anything underwater.

Our results were interesting because when we compared what was in the muscles with what we had seen in the gut contents, it looked like tadpole diet is more a case of ‘you are some of what you eat and not necessarily the most obvious or biggest thing’.

So, while pieces of plants or long strands of algae were often jam-packed in the tadpoles’ guts taking up a lot of space, they were not contributing much nutritionally. It looks like the really small and least obvious thing growing underwater is a high quality, nutritious snack supporting the growth and health of bigger lifeforms!

There is definitely more to know before making strategies for wetland management that will support lots of good tasty biofilm and in turn support tadpole growth, but we’re starting to build evidence for what we only suspected before. For example, see Altig et al 2007, Schiesari et al 2009, Schmidt et al 2017. And I definitely suggest doing both gut content dissection and stable isotope analysis, if you want to find the important end of the tadpole food-web.